(I repeat today what has become an Easter Tradition for me – my little story about Pontius Pilate and the Lord. Some, over the years, have commented on how real the death scene feels. I took it almost verbatim from an actual event I participated in.

What follows is fiction. I used the literary device of an archaeological find, but it is fiction entirely from my meditation on the Crowning of Thorns. This is NOT definitely what happened with Pilate, but merely my meditation on what MIGHT have happened with him. The historical events described prior to Pilate’s departure from Jerusalem are largely taken from the histories of Josephus, though I have used some less reliable ancient historians for sources, as well. Actually, Pilate vanished into the mists of history after his departure from Jerusalem. Most think he receded from view somewhere in Gaul, rather than in the tiny of town of Pyrgi, as I have set him here.

Please enjoy this little tale. Let it give you food for contemplation. If you comment to tell me that this mystic or that saint imagined it differently, you might be missing the point. There are a multitude of such speculations. We are called to enter in, to ponder the Mysteries of the Rosary. That is what I do with these little stories. I invite you to do the same – and I won’t be the least bit upset if your imaging differs from mine.-CJ)

By Charlie Johnston

The document that follows is a letter from a collection of parchments found sealed in an ancient vase. It was discovered in the modern-day Italian City of Velletri. The collection apparently dates to the reign of Claudius Caesar and was probably hidden during the tumultuous and destructive reign of Nero. It is written in Latin with a generous sprinkling of Aramaic phrases. If authenticated, its significance is obvious. From internal clues, we date it preliminarily to the spring of 39 A.D.

Dear Portia,

Pilate is dead.

I am sorry to tell you so bluntly but, in truth, it is a relief. He took ill with that awful consumptive disease when winter set in and has suffered grievously. These last three weeks he has been almost constantly delirious, wracked both by agonizing pain and unceasing night terrors. You cannot know what a trial it has been. Were it not for my brother’s wife and a friend we made here in Pyrgi, I do not think I could have borne it at all.

We were never happy in Judea. Oh, Pilate was proud when he was named procurator, to be sure. When we marched in with our cohort to take residence, he flew the imperial standards high and with pride. We had heard the Jews could be a contentious lot, so Pilate thought we would get off on a good footing by establishing residence among the people. But the trouble began immediately. The Jews went into an uproar, claiming that the image of the divine Caesar on our standards was a blasphemy to their God. They claimed that the fortress we occupied, Antonia, was part of their temple – and our residence there a desecration. Their behavior was so insolent and riotous Pilate asked his predecessor, Gratus, to delay his departure a few days to give us counsel.

Gratus warned Pilate that the Jews were zealous and ready to revolt on anything touching their religion, but were otherwise dutiful and productive subjects. He named some members of the Sanhedrin, the Jewish high council, with whom he had made useful alliances.

They would, he promised, be as zealous as we are in enforcing imperial law and extracting taxes if we gave them leave concerning their religion. Pilate suggested it might be time to demonstrate who was ruler and who was ruled here, but Gratus firmly discouraged such a course. We would find to our sorrow, he assured us, that the policy of Rome, itself, was to yield to the Jews on matters concerning their religion. It was the only issue that sparked rebellion and Judea was too important a holding to toy with when it was so easily appeased without detriment to genuine Roman interests.

So Pilate sent the standards off to Caesarea and we vacated the fortress. We moved into a castle on Mt. Zion that was more spacious, anyway. That became the source of yet another uproar. Pilate hung the golden shields in honor of our gods on the castle. Once again the Jews cried, “Desecration,” because the shields were engraved with the gods’ names. It set Pilate into a fury. He had respected their god, he reasoned, so they could return the favor and show a little respect for our gods. This was our castle and Pilate was the delegate in Judea of Imperial Rome. He refused to be moved. The Sanhedrin appealed to Rome. Gratus was right. The decree we received ordering the shields removed was signed by Tiberius, himself.

After his anger subsided, Pilate sought a means of improving his relations with the contentious Jews. He began to meet regularly with the Sanhedrin to seek their counsel. A common theme was the shortage of water in the city and the difficulty many had in transporting it and keeping their crops irrigated during the dry season. The council had heard of the excellent aqueducts we had in Rome and wondered if a similar project might be attempted in Jerusalem.

Pilate was delighted. He contacted Rome and obtained engineers for the project. Oh, what a wonderful time it seemed! Not only were we bringing water to our subjects; Pilate personally ordered that as many Jews as possible be hired to help in the construction. But this became the greatest source of controversy yet. Some priests complained that temple revenues were being used in the project. The Sanhedrin ruled that temple revenues could only be used for sacred purposes. Pilate was outraged. The bulk of the

project was being financed from his own treasury. He thought the Sanhedrin malicious, petty and ungrateful. He went before the high council and asked what could be more sacred than protecting the people from the effects of drought. He demanded to know on what grounds they could refuse to contribute to what would work primarily to their benefit. The council decided it would support a new levy on the people, but was adamant that its own revenues must remain untouched. Pilate cursed them and walked out. The Sanhedrin then inflamed the people into an uproar and the project was abandoned.

After that Pilate kept away from the Jews. He sought no further advice from the high council, nor did its members receive welcome when calling on him, even on matters solely devoted to the empire. He became very harsh in matters of imperial law and exacting the tribute. What else was he supposed to do? Every time he reached out to them, the Sanhedrin twisted it against him. He hated them.

The final straw came in the trial of the Jewish holy man, Jesus. It was right around this time nine years ago, when the Jews celebrate the Passover. People had been overjoyed when Jesus had come into the city the previous Sunday. He had gained much renown as a healer and miracle worker. Many of the common people had started calling him their king, the Messiah. This disturbed Pilate. But he also received reports that the Sanhedrin was enraged at the man, so decided to look further into the matter. Jesus had apparently beaten and chased many of the council’s revenue collectors away from the temple – and this at their most profitable time of year. That soothed Pilate. He figured any enemy of the Sanhedrin couldn’t be all bad. So he told his informants to keep him apprised of what was happening in the city.

Pilate learned a lot over the next few days. The Sanhedrin had once tried to recruit Jesus to their ranks, but he had spurned them, calling them hypocrites and snakes who bled the people rather than helping them. Shocked, the Sanhedrin returned his contempt in spades. They sent lackeys out to try to trick Jesus into saying something they could denounce him for. But his answers were too clever, always leaving the lackeys looking like fools. Even worse, some of the agents the council sent had defected and become adherents of the man. The more Pilate learned, the more he liked this Jesus, but tensions were getting so high he feared there might be an open confrontation before the festival was over.

Before dawn on Friday we were awoken by our attendant, who told us a group of Jewish officials was demanding to see Pilate immediately on a most urgent matter. I had had a terrible dream that night. I had seen this Jesus standing meekly on a hill, his face a mask of sorrow. All manner of furious people, their faces contorted in rage, were hurling themselves at him with swords and clubs. And all who reached him crumbled to dust as soon as their weapons touched him. He wept copiously, begging them to stop that he might help them, but they just kept on coming, destroying themselves in their rage. In my dream, Jesus looked deeply into my eyes, tears streaming down his sorrowful face. I shiver now at the memory of that gaze.

I was in tears, myself, as Pilate dressed to go downstairs. I told him please; please…if this had anything to do with that holy man, Jesus, have nothing to do with it. He must not harm Jesus. I told him of my dream. He told me not to worry; he would send the Jews away.

When Pilate got downstairs the whole Sanhedrin was waiting for him. They were in an uproar – and it was about Jesus. The council was making all manner of wild political charges against the man and demanding he be put to death. I’m sure my face paled when Pilate came up to tell me. He said he had to go or there would surely be a riot.

He knew the council hated Jesus and only sought to destroy him because of the following he had built, a following that threatened to topple their own authority. He said he would drag things out until midday when the people would begin to fill the square – and the weight of the people, themselves, would force the council to back down.

But he was home again in just a few hours, shaken and pale. He had spoken with Jesus. The man was not at all what Pilate had expected. He said he kept thinking of my dream as he spoke with him. Pilate said Jesus seemed incredibly sorrowful, but not at all afraid, so much so that Pilate thought it bordered on insolence. At first Jesus would not respond to his questions at all. Irritated, Pilate asked Jesus if he knew he had power to condemn or to spare him. Jesus looked deep into his eyes with a terrible pity and told my husband he had no power at all save that which was given from above. It stunned Pilate, so he asked Jesus if he was a king. The holy man did not answer directly, but said his kingdom was not of this world.

That was enough for Pilate. Clearly, this was no threat to the empire, just to the Sanhedrin. He decided on the spot to release Jesus immediately. But when he went into the courtyard to announce his decision it was already filled with people. To his horror, Pilate realized the Sanhedrin must have filled the square with its own people during the night. When the common people began to arrive at mid-morning they would be crowded out. He went to his seat before the judgment table and announced he had found no fault in Jesus and would release him. The crowd roared, demanding his crucifixion. All Pilate could do was play for time. So he claimed there were jurisdictional issues and sent Jesus to Herod for questioning. Herod questioned him and sent him back. Again Pilate went out and told the crowd that neither he nor Herod had found any fault in the man. But the crowd shouted all the louder, “Crucify him!”

Pilate feared another revolt might get him recalled to Rome in disgrace. Desperate to damp down the tension, he sent Jesus off to be scourged, hoping it would satiate the crowd’s bloodlust.

I told him I was going back to the square with him. His face went absolutely white and he said no, I must not go there. But I was adamant. Finally he said I could go as long as I stayed out of sight of the crowd in the side hall of the west entrance.

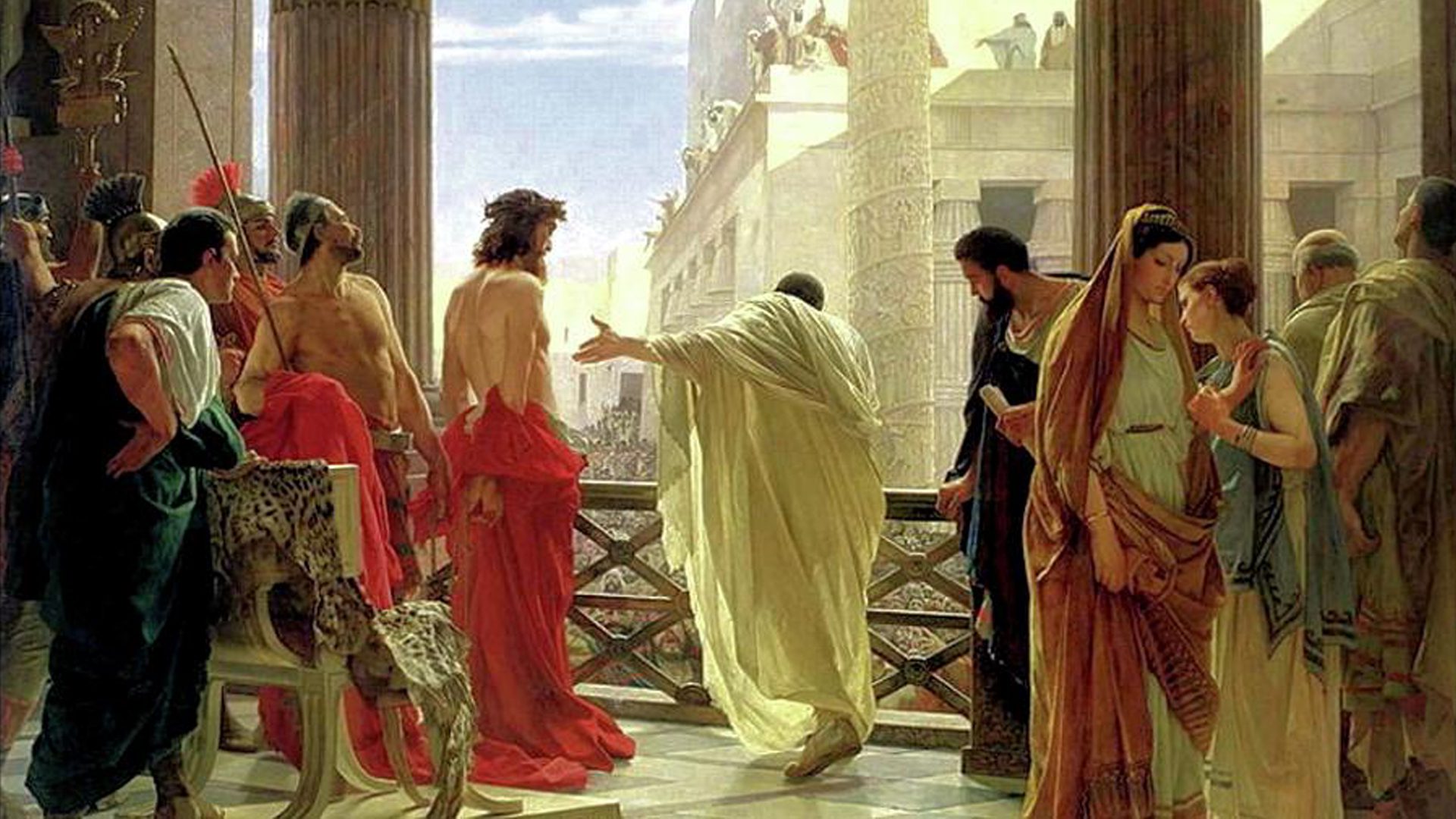

After I was seated, the guard brought Jesus in through the east entrance, directly across from me. Portia, I have never seen a sight as terrible and terrifying. His face was battered and swollen, so purple I didn’t at first notice the bright red blood trickling from his forehead. They had forced some sort of cap of thorns and briars onto his head. It was these which, forced into his forehead, caused fresh blood to trickle. They had adorned him with a robe of the royal color, which matched the color of his face. In his right hand they made him hold some sort of stick. I finally realized the horrible joke; they had made a mock king of him. Pilate staggered when he saw him. I thought my husband would faint. He turned back to me with a look of sick desperation and, with one hand, motioned firmly for me not to move from where I was at.

Pilate leaned forward and gripped the table of the judgment seat with both hands. After the stricken look he had given me, I was astonished at the calm command of his voice as he addressed the crowd. He told them firmly he had found no fault with the man and was going to release him. The mob’s cry hit us both like a fist. “Crucify him,” they screamed. Pilate looked at Jesus, then back at me. From where I sat I could see something the crowd could not. My husband’s knees were shaking uncontrollably. He sat down. After a moment, I could see an idea had occurred to him. He rose again and spoke.

“It is our custom to release a prisoner each year on the occasion of the Passover festival. Whom shall I release to you; Jesus, called the Christ, or Barabbas?” he asked the crowd.

Oh Portia, how I admired the cleverness of our Pilate at that moment! Barabbas was a murderous insurrectionist who cared little whether it was Jews or Romans; men, women or children that he murdered, as long as he was killing.

Confronted with this choice the people would have to choose Jesus. The square was silent as the nature of the choice sank in. And then the cry began. “Free Barabbas!” It rose to an insane, rhythmic chant. Pilate staggered again and fell back into his seat. I looked across at Jesus. Bloody and battered as he was, he looked at my husband with such sorrowful pity you would have thought it was Pilate’s fate which hung in the balance. Then Jesus looked at me and, through the gore, I saw the man from my dream. I moaned in terror, sure we would all die there that day. Pilate looked over to me, his face sick with desperation and panic.

“Shall I crucify your king?” he pleaded with the crowd. Then I heard the voice of the high priest, shrill with malice and rage, cry triumphantly, “We have no king but Caesar.” I could not see the high priest from where I sat, but I knew where he must be; on the receiving end of the most smoldering gaze of murderous contempt I have ever seen on my dear husband’s face. The chant of the mob continued, “Crucify him, crucify him!”

Anger at the high priest galvanized my husband. He ordered silence in a voice that clearly threatened to do to the crowd what they would do to Jesus if they failed to obey. He told them he had found no fault in the man, then turned to the guard and ordered that a basin of water be brought before him. He stood waiting for the basin, his stare daring the crowd to say it, to go ahead and break this sulfurous silence with their murderous cry. The mob did not accept the invitation. When the basin arrived Pilate solemnly washed his hands. “I am innocent of this man’s blood,” he told the mob, “Upon you it shall be.” I heard the high priest’s voice respond with gleeful triumph. “Upon us, let it be,” he cried.

I was horrified by the rage and loathing that filled my husband’s eyes; even more so by the look of terrible pity Jesus gave Pilate as the guard took hold of him to lead him away. When he came back into the hall to me, Pilate ordered a guard to fashion a sign to be affixed to Jesus’ cross. He ordered that it read, “Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews.”

After we got home and the guard had been dismissed, Pilate spoke to me. “When they brought him in I understood immediately the horrible joke,” he told me. “But as I looked in Jesus eyes, something happened. There was a brilliant radiance surrounding him. I saw power coming from him like rays of the sun. He was majestic and noble and his eyes were filled with compassion for me. For me! Can you believe it? Here the mob is crying for his head and he is looking at me with compassion. I could see he is a king.” Pilate shook his head briefly in confusion, then corrected himself. “No, he is not a king. He is the king.”

“How, then, could you condemn him?” I gently asked.

“I did not!” Pilate said to me with sudden fury, then caught himself. “He told me his kingdom is not of this world and I believe him. Whatever world he is from is more than this one. They will not be able to kill him. The joke is on them. The Sanhedrin has tormented us from the very day we arrived, and now they torment this king. But they have reached too far. This one they can’t contain. They will see. It will be just like your dream. Their malice against him will break them, not him.”

Pilate was so earnest and agitated, I left him alone. To speak at all was to trigger an intense outburst from him. So we waited in uneasy quiet for news. Late in the morning the high priest came in a rage, demanding to see Pilate. He complained that the sign Pilate had prepared should have read, “He claimed to be king of the Jews.” Pilate gazed at the high priest with savage joy and contempt as he said, “What I have written, I have written,” then had him thrown from the castle. He grinned at me in satisfaction. “Imagine their terror when they discover they really have set themselves against their king.”

But it was not to be. Late that afternoon we had a terrible earthquake, followed by a brief, furious storm. Both Pilate and I feared my dream was coming true. Just as the storm died, a messenger from the guard came to inform us that Jesus was dead. Pilate was thunderstruck. He thought sure that Jesus would somehow turn the tables on the council. Now he was terrified. After seeing the kingly radiance surrounding Jesus, Pilate thought the business of the basin was a clever and stately way of shifting all responsibility over to the Sanhedrin. He had actually used the basin as a message to Jesus: the message to the crowd was an afterthought. But now that his impossible hopes had been dashed, he knew the basin did not clean his hands of Jesus’ blood. He was terrified.

That evening, a man named Joseph, who Pilate thought was allied with the council, broke the paralysis that had settled on my husband. This Joseph asked permission to take the body of Jesus and remove it to his family tomb. Pilate was suspicious. He thought it a trick by the Sanhedrin to further desecrate Jesus. But several women had accompanied Joseph and awaited him in the outer court. When they were told Pilate would not release the body, they wailed with such intense and piteous grief that my husband was convinced they must have loved the man, Jesus, and so released him to their care.

The next morning a priest came to ask Pilate to set a guard at the tomb. He explained that Jesus had told crowds that he must be put to death, but would rise again on the third day. The council feared his disciples might steal the body and create an even bigger following for him in death than he had in life. Much to the priest’s surprise Pilate immediately, even eagerly, agreed. The priest slyly observed that the high priest would be very pleased to know that the procurator had thought better of the matter.

“You tell that viper if he ever ventures into my courtyard again he will meet the same fate he contrived for your king,” Pilate spat at him with such fury the priest did not dare argue that Jesus was not their king.

After the priest left, Pilate shook with emotion. What emotion, I could not tell. It could have been fury, joy, fear or some intense mixture of these and more. “I told you,” he said to me, “Death cannot hold that man. He is a king and I will not let the council get hold of his body to defile it before he has accomplished his purpose. The council wants the guard to keep his disciples out. I set the guard to keep the council out.”

His eyes blazed with such intensity I feared my husband might be taking leave of his senses. I took great care to soothe him. He took care to order the guards he had appointed to keep him apprised of any news, and to defend to the death any attempted intrusion into the tomb.

It was just after noon the next day when one of the guards came, shaking with terror, to report that somehow the body had been stolen right out from under them.

Pilate looked at me and remarked that this was the third day. He ordered the guardsman be brought some refreshment, then kindly, but intensely questioned him. The guard swore the cohort had not been drinking or carousing, as they were fearful about incurring the procurator’s wrath. They knew how important this was. The messenger reported they had been standing guard when a brilliant light bloomed in the darkness, blinding them. It had seemed only a moment, he said, but when their sight returned they were all on their backs and it was dawn – and the rock had been moved from the tomb. Pilate asked why it had taken so long for them to come tell him. The guard responded that they had been frightened the procurator might have them executed and so had argued among themselves on whether to send one to tell him or to flee. Pilate asked if there was any other news he should know. The guard’s whole body seemed to wither in misery as he reported that some of the women who had been with Jesus claimed he had risen and even spoken to them.

Pilate was delighted. He assured the guard that none of them would be punished, that they should just keep quiet about what had happened, neither confirming nor contradicting any rumors that arose. The guard gloomily protested that already some of the council were spreading rumors that the guard had been drunk with carousing. This delighted Pilate even more, so much that he ordered three months wages be given as bonus to each of the four guardsmen, while re-iterating his order that they say nothing and completely ignore whatever rumors the Sanhedrin put out.

After the guard left I asked Pilate why he was so pleased.

“Don’t you see,” he asked me. “If the council is putting out such rumors it proves they do not have the body. They are trying to contain the damage. Their constant schemes have fanned the flames of public resentment against us since we arrived. Every effort we made to improve relations they used as kindling to fire the flames even hotter against us. But now they are caught in their own trap. Every rumor they spread, every lie they tell is another piece of wood they lay on the cairn that will consume them.”

I asked Pilate if he thought Jesus was really risen. He pondered for a moment, then smiled and said whether he was or whether he wasn’t, the Sanhedrin would have much more to worry about now than how to make our lives a misery.

Over the next few months rumors swirled throughout Jerusalem about where Jesus had been, who had seen him, who he had talked with and what he was doing. It was even reported, with witnesses attendant, that he had preached to a group of hundreds of people at a single time. The council was beside itself. I think Pilate was hoping Jesus might come to us and offer some words of comfort and hope. He certainly never tired of summoning witnesses to recount for him all the details of the latest sighting. Finally, word came that Jesus had stood amongst some of his followers and vanished into the heavens before their very eyes, and the rumors died down.

That, however, was not the end of the matter. More like the beginning, if you want to know the truth. The followers of Jesus were bolder than ever. They took to calling themselves The Way and holding forth in synagogues throughout Jerusalem. The Sanhedrin was constantly bringing members of The Way up on charges. Nothing delighted Pilate more those last few years than to tell the furious priests to “…see to the matter, yourselves” and not to trouble him on matters pertaining to their religion.

Of course, our relations with the Sanhedrin were forever poisoned after that. Not that they had been much to speak about before, but after that Passover it became a constant struggle. The Sanhedrin was constantly trying to undermine Pilate with Rome and Pilate was constantly trying to undermine the Sanhedrin with the people. It was ironic that during those last few years Pilate achieved a rather popular following among the growing segment of Jews who identified themselves with The Way. Both made the Sanhedrin squirm, though I think Pilate enjoyed it more than members of The Way did. Eventually, though, we were summoned to Rome to answer charges that we were conspiring with the rebellious sect known as The Way to overthrow the Sanhedrin. It wasn’t true, but certainly Pilate did always rule in favor of anyone he knew – or even thought – to be connected with The Way any time the council brought them up on charges.

In many ways it was a relief. Our time in Jerusalem had not been pleasant. After proving his loyalty, Pilate hoped to receive another, more auspicious posting. He would even have been content with a return to the Legion with a favorable command, though we had grown very fond of each other over the course of our troubled encounter with Judea and did not want the separation that re-appointment to the Legion would inevitably bring. Unfortunately Tiberius died while we were en route to Rome and the new emperor, Caligula, did not consider hearing our case a priority. We went to stay with my brother and his wife in Pyrgi, just about a day north of Rome, to await the emperor’s pleasure. To our surprise, The Way had established a few footholds even here, in the heart of the empire. We met two adherents who said they had been in the courtyard on the day of the great drama. One, Joses by name, came to visit us quite regularly, occasionally bringing a friend or two. Joses and Pilate became fast friends and loved to talk at great length about Jesus. I thank God for it. When Pilate took ill a few months ago, Joses took it upon himself to stay with us and help me care for my husband.

You have to understand, Portia, that over the last few years Pilate was not the same man you knew from your childhood or his early days with the Legion. He never slept well anymore and his days were ever more listless. The only time he seemed his old self was when Joses came around. Truth is, Pilate had become consumed with thoughts of Jesus and what he could have done differently that day. He feared he had failed the only real king he had ever met. It ate at him. Joses swore that he had been among the crowd that Jesus had preached to after having risen. I think that, more than anything, sealed Pilate’s attachment to him. Pilate asked him why the members of The Way didn’t hate him, even seemed to enjoy coming up to visit him, when they both knew that whatever his protestations, without his approval there could have been no crucifixion. Pilate’s voice trembled as he once told me that Joses had explained that if Jesus was to conquer death and rise, he must first die. To some in The Way, Pilate was a curiosity. For others, even though he was a Roman, he had spoken with Jesus on that last day and that meant something. For those who had been there, Joses said, yes, Pilate had a hand in Jesus’ death. But his was the only hand that day that had seemed unwilling. And more, Joses told him, every friend he had brought said afterward that they could feel the grief of it still hanging on Pilate like a shroud.

Sometimes in the night, Portia, I would wake to hear Pilate muttering, “Your king is innocent,” or “I find no fault in him.” He would toss and turn throughout the night. Even on the good nights, the bedclothes would be soaking in the morning. One terrible night I woke to hear Pilate screaming, “I wash my hands of it. I tell you I wash my hands of it!” I had to wake him to keep him from disturbing the whole household. When I did he kept looking in all directions in frenzied panic. He shrank against the bedpost and didn’t recognize me. He kept begging, “Please, please…” and wouldn’t suffer me to touch him for some time. It took me hours to calm him. Finally he drifted back to sleep and did not awake until late the next afternoon.

Joses told me that Pilate constantly asked him if he thought Jesus could forgive him. Joses tried to reassure him that Jesus already had, but Pilate would always mist up in disconsolate grief, telling him, “I could have stopped it, but didn’t. I should have stopped it, but didn’t. Oh why, oh why, oh why didn’t I stop it? I’ve been lost ever since.” It grieved Joses that Pilate could not understand how forgiving of weakness Jesus is. It is malice that destroys a man, Joses said. He kept trying to tell Pilate he had more to fear from his hatred of the Sanhedrin than of the role he played in Jesus’ death. But Pilate would not hear any defense of the Sanhedrin – and could not accept that Jesus would ever forgive him for letting them take him to Golgotha.

When the sickness came, Pilate got worse. He laid in bed and kept begging Joses to ask Jesus to come and forgive him. He said he could not believe he could ever be forgiven unless Jesus came, himself, to tell him. Over and over, it was all he would talk about, then sob uncontrollably. In these last three weeks, he was in constant agony. He could neither sleep, nor stay awake. He was either quiet and labored or raving. “Jesus, forgive me,” he would plead, “Come tell me you forgive me,” and then great, wracking sobs that tore my heart out.

Joses would sit with him sometimes and send me away to give me a break, but I could tell it was hard on him, too. Four days ago, he had to go away for a week, but said he would try to get back early. Thank God he got back late yesterday afternoon. Ever since he had left, Pilate kept asking me, “Claudia, why are you doing me this way?” and groaning in agony. It was a constant accusation. When Joses arrived he found me crying in the garden. I collapsed onto his chest weeping as I told him what had happened. I told him I knew Pilate was not in his right mind anymore, but it hurt so bad that, even in his delirium, he should think I was doing this to him. I cried and cried and cried some more. I told him I had to go back up to Pilate; I couldn’t leave it like this, but I didn’t know if I could bear it.

Joses cradled my chin in his hands and wiped my tears off. “We’ll go up together, Claudia. You know he doesn’t mean it and he needs you so much now. We’ll see him together and you’ll be strong,” he told me. It was such a relief to have Joses with me as we went in. Pilate started stirring immediately and then woke, confused and feeble.

“Look,” I said. “Joses is here to see you. See, Pilate, your friend Joses is with us.”

As soon as we entered I saw that Joses had started silently mouthing prayers. It seemed to give me strength. Certainly, having Joses here gave me something to focus Pilate’s attention on other than me or his pain. I kept telling him that Joses was here, over and over. It felt silly to keep repeating it, but I couldn’t help myself. It had become a mantra against the darkness. Joses had his own mantra. He did not cease mouthing his silent, urgent prayers. To the astonishment of both of us, Pilate started struggling to sit up. He didn’t have the strength for it, but was determined. Joses did not cease his silent prayer, nor I my cheery announcements as we helped move Pilate into a sitting position. Joses put his arm behind Pilate to support him. When Pilate was up, his head slumped limply on his chest and his arms hung as limply at his sides. He took deep, struggling breaths, as if he had just finished some fearsome effort which, I guess, he had. After a few minutes, Joses interrupted his prayer long enough to say, “Claudia, he’s trying to tell you something.” I looked down and saw Pilate’s fingers twitching purposefully at me. My heart sank, but I leaned in to him. As I did, he grabbed my arm with a strength I would not have thought possible in that skeletal frame. “I…I love you, Claudia,” he whispered in a gasp. Tears flooded my eyes. It was all I could do to keep from bursting into sobs. Instead I replied, “I love you, too, Pilate.” But as I started to sit back up, his grip was all the stronger and more insistent. He had neither lifted his head from his chest nor opened his eyes during this effort. Again, he took deep, gasping breaths, gathering his strength for something more. Twice more, he told me he loved me. After the last, without lifting his head or opening his eyes, the faintest smile of contentment smoothed his face. I told Joses I thought he was ready to sleep again.

We gently laid him back down. Oh what a lovely sight he was! His breathing was deep and strong and quiet, and the faint smile of contentment remained on his face. I told Joses, with no little amazement, that it was the first peaceful sleep he had had in months. Joses smiled and said, “He needed to tell you how much he loves you.”

We went to the anteroom and had some tea sent up. We talked quietly into the wee hours of the night. Every time I went to look in on Pilate he was breathing deeply and peacefully. What a blessing! Sometime during the night, he slipped quietly away. I think Jesus must have come before Joses and I went up to him last evening.

Your brother is at peace, Portia. I know it with certainty. And how glad the knowing is!

Your sister-in-law,

Claudia Procula

If communication goes out for any length of time, meet outside your local Church at 9 a.m. on Saturday mornings. Tell friends at Church now in case you can’t then. CORAC teams will be out looking for people to gather in and work with.

Find me on Twitter at @JohnstonPilgrim

0 Comments