When I came out of the theatre after watching The Shift, I was only thinking one word: refund. Not so much the ticket price, but the two hours.

By the next morning, I’d completely changed my mind. Talk about a shift. This is a movie that sticks with you. I must say, I like a movie that doesn’t give you all it has on the first date. You have to probe, you have to ponder. Probably no one was still thinking about the levels of meaning in Barbie the day after they saw it. But The Shift will continue to work in your mind, and reveal more of itself the longer you think about it.

First of all, the movie is an allegory. Taking it literally will rob you of some of the meaning. For example, the whole idea of lives actually being lived in multiple universes at once is profoundly un-Christian. Every human is a body-person, and the life of any particular person is in that one body; it can’t be parsed. The Incarnation guarantees this integrity.

So how can a movie conceived and produced by a Christian studio feature multiple bodies in multiple universes? The answer is that it’s an allegory, and a rich one. Each alternate universe is a picture of the world we create when we sin. As many different sins as there are, that’s how many universes could be posited. And they’re all dreary, dangerous and dull. That’s a worthy lesson about the effects of sin.

The alternate “sin world” in the movie was a perfect portrayal of the world globalists are trying to create for us: starving, demoralized people who will do nearly anything to escape the hell of daily life, including a media experience that mimics the Metaverse; storm-trooper police with reflective face shields that completely hide any semblance of humanity; crime, filth, oppression and poverty. Bibles are outlawed, as well as any mention of God. People can be arrested or shot for anything or nothing.

The potential familiarity of that hell-world was the main reason I practically ran out of the theater when the movie ended; it hit just a little too close to home, and scared me in its plausibility. Was it intentional that the world created by sin looks very much like Democrat-run inner cities?

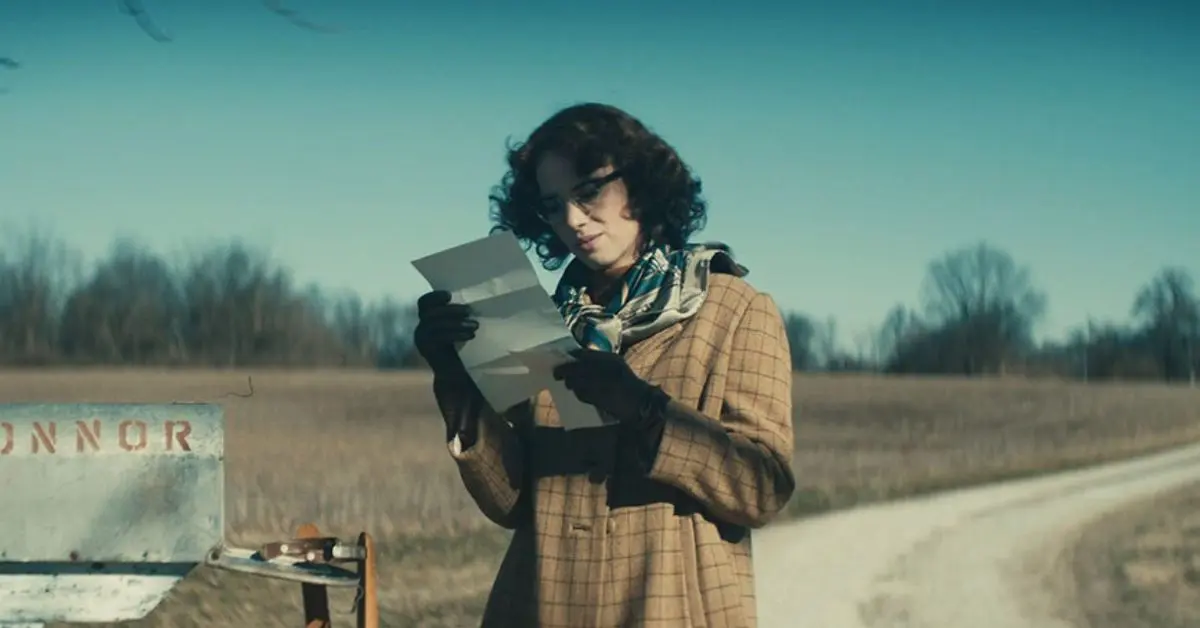

When the movie begins, that dark world is not yet visible. The protagonist, Kevin, a man deeply in love with his wife, is targeted by The Benefactor, a slick, well-groomed man in an expensive suit whom we soon realize is the devil. The Benefactor sees qualities in Kevin that he’d like to use in his mission, but Kevin, who is at least a casual Christian, knows enough to pray when the devil is pounding at him. His prayer infuriates The Benefactor, who seems to thus be defeated, but nevertheless, Kevin is transported to that dark world of bleak hellishness that looks like an inner city in a dystopian America. (It was filmed in Birmingham, Alabama, which is, in fact, a Democrat-controlled city.)

I had to visit that scene over and over again to make sense of it. If Kevin did the right thing (pray to God) with enough fervor to anger the devil, then why is he in hell for the rest of the movie? I didn’t figure it out until the next day, because it didn’t involve sin the way I normally think of it. Kevin didn’t lie, steal, murder or commit adultery. He was a good man, a kind man. The sin he committed was subtle.

The sin is disregard, something we all do every day. We disregard the distress of the unborn, the trafficked, the unjustly imprisoned, even members of our own families. We do it to survive mentally, to be able to go to work the next day, to function in our daily lives. We do it because we don’t believe we can survive the pain that is all around us. But what if that disregard is enough to create a hell we can’t escape?

In Kevin’s case, it was, and it shifted him to a world of emptiness and pain. No matter how many times he gave his meager food to others, or risked his life to write down half-remembered Scripture verses, no matter how many good works, he was still in hell. But he retained his humanity because of his stubborn love for his wife, and his desperate attempts to find a way back to her. Love saved him long enough that he could finally make a choice, in extremis, to undo the harm he’d originally caused. Love gave him the chance for redemption.

The dark world that Kevin is trapped in, the one that looks like where we are headed if we don’t do something quickly, is the hell we build with selfishness. The Benefactor says that clearly, in case we missed it: all sin is selfishness. We are trapped in hell until we finally make a heroic gift of ourselves to another. Perhaps the serial hells are what it takes for some of us (me) to finally be so sick of selfish choices that sacrificial love looks like the obvious and joyful way out.

In the climactic scene, The Benefactor and Kevin word-wrestle about God and the absence of God in that dark world where Kevin is trapped. The Benefactor taunts him: why doesn’t God come? Why doesn’t God answer? It’s the classic problem of evil: where is God?

And like any serious philosophical reflection on that question, there’s not a direct answer. God, like The Shift, and like the Book of Job which it resembles, is not an easily wrapped-up sermon in a box. Our journey to Him is hard-fought, dangerous, as if in a fog, with the outcome not certain or guaranteed. It’s a walk of fear and trembling.

If you watch this movie, settle in for the long game. Don’t expect to love it at first sight. Let it work on you.

Cinematic detailers will recognize Paras Patel and Elizabeth Tabish (Matthew and Mary Magdalene from The Chosen) and Sean Astin (Samwise Gamgee from The Lord of the Rings.) If you watch closely, you’ll also pick out Jordan Walker Ross (Little James from The Chosen) in a crowd scene. Neal McDonough, who plays The Benefactor, is one of the best “bad guy” character actors in the business.

As of today, December 8, The Shift continues in theaters. It will be available on the Angel Studios app and website after its theatrical run. The production budget was $6 million, which was already recovered in the first week box office receipts. It’s rated PG and scores 87% with audiences on Rotten Tomatoes.

To find a theater near you, watch the trailer and buy tickets, visit >

Sheryl Collmer is an independent consultant for several non-profit organizations. She holds a Masters in Theological Studies from the University of Dallas, as well as an MBA. She lives in the diocese of Tyler, Texas and also serves as CFO, co-coordinator of Region 8, and national news editor for CORAC.

0 Comments