OPINION –

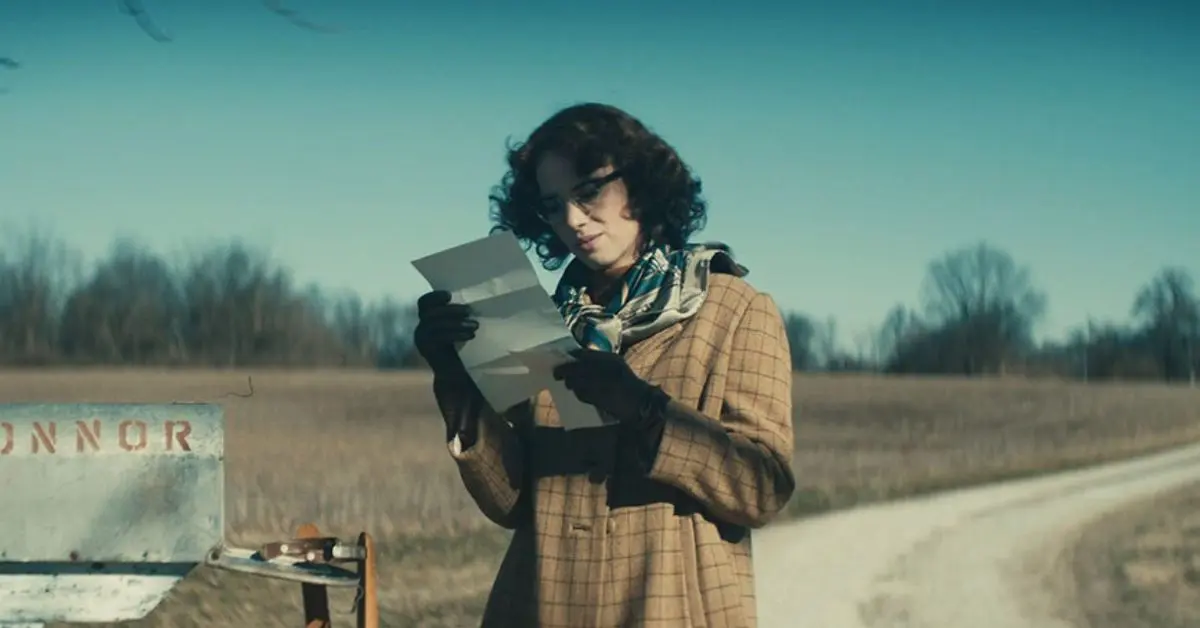

I appreciate that cigar culture has finer points, but the smell of cigars still makes me queasy. Likewise, Flannery O’Connor. She is an acquired taste, and this review of Wildcat, the new biodrama of O’Connor, is written from the perspective of one who has not thoroughly acquired it. I daresay I’m not alone on the periphery of her fandom. Most people, when asked if they have read Flannery O’Connor, make a face.

But there’s a Flannery O’Connor society that holds posthumous birthday parties for her. “Flanatics” can tour her home in Georgia, go on Flannery pilgrimages, and mail a postcard with a Flannery commemorative stamp. She’s consistently listed as one of the greatest Catholic authors of all time and, by the secular Oxford American, one of the best Southern novelists of all time.

So you see, Flannery O’Connor is good. And I have choked her work down at intervals throughout my Catholic life, always wondering what I was missing. Why is she the GOAT?

This film gave me a clue; not an answer, but a clue. The movie succeeds at one of the great tasks of storytelling: submerging the audience so deeply in a particular place and time that it’s a jolt to resurface. Wildcat is named after one of Flannery’s early short stories, not widely considered one of her best; but it is an engaging title nevertheless. In her strange, understated manner, Flannery is indeed a literary wildcat. The movie captures the feral nature of her stories and hints at Flannery’s motivation by meshing her life story with vignettes from her short stories.

Sadly, the movie truncated the stories, so the moments of redemption that are the crowning glory of otherwise dark, twisted tales were either omitted altogether or gelded. Without some background reading, an audience would never know that Flannery was a deeply-formed Catholic whose vision was entirely distilled by the Church’s understanding of human nature.

The versatile Laura Linney plays Mary Flannery’s mother, Regina, a middle-class Southern woman heavily saturated with the conventions of Southern society and definite ideas about what is acceptable to say, do, and wear.

Flannery could not have been more mutinous, with her untamed hair, old black loafers, and heavy browline glasses that scream of low-level clerkdom. She spoke without the filter of well-bred Southern women; indeed, she was determined to extract that filter like a dentist pulls a bad tooth.

In addition to Flannery’s own mother, Laura Linney also portrays the trailer-trash mother who sells her mute daughter to a one-armed vagabond in The Life You Save May Be Your Own, the clueless mother in Good Country People who is taken in by an atheist Bible salesman with a fetish for prosthetics, and the smug Christian woman of Revelation, so thankful that she’s not of the lower classes. With Linney portraying all these women, it’s implied that Flannery’s mother was of a piece with them.

It was jarring to see the lovely Linney, who was all pearls and cream when she used to introduce Downton Abbey on Sunday evenings, descending from a trailer in Goodwill pedal-pushers, speaking in an accent like rusty hinges. I’m now convinced Linney can do absolutely anything as an actress.

In this bio-fiction amalgam, Maya Hawke plays Flannery, plus various odd characters from the short stories: an angry Jeremiah, a one-legged Ph.D. philosopher, and a violent prophetess against the genteel racism that manifests as patronage.

There is such crossover that it’s unclear where the biography ends and fiction begins. Was Flannery as rebellious toward her mother as the acne-faced girl in Revelation? Was Regina as socially rigid as the pharisaic woman who rejoices in her superiority? When it’s Maya Hawke and Laura Linney all the way down, it becomes hard to tell.

Maya Hawke is the daughter of cinematic powerhouses Uma Thurman and Ethan Hawke. (Ethan directed and co-wrote the film). Maya is at the leading edge of her career and couldn’t have picked a better veteran than Linney for a guide. It would have been so sweatless to make Flannery a caricature, but Maya portrays the complex author with delicacy. Considering that the Hawkes nearly ditched the project when they found what they considered to be racism in some of Flannery’s letters, the portrayal is touchingly affectionate.

Modern critics of O’Connor have tended to put her writings through a finely-set racism detector, but Flannery wrote about human beings with race in the background. Racism reduces people to one dimension and Flannery never, ever did that. I would even say she was anti-racist, because she dealt with her characters in their ignominious fullness, not as a single aspect of outward appearance.

It may be Flannery’s greatest strength, as both a writer and a Catholic, that she considered people comprehensibly: dwarfed by pettiness, slaves to convention, even pawns of evil…but always redeemable, even if violence had to be the catalyst.

There is a convincing “Southern Gothic” feel about the movie, with the fictional scenes a colorized black-and-white, softening the seediness that was often Flannery’s setting. That tone situates the film in a definitive era, an age that was ending when I was coming up, before media became more followed than life, before driving replaced walking, before the Mass was brought down to our level. The decade of the Sixties changed everything, and Flannery’s short stories rode the wave just before it curled over.

At the time she was creating, she already perceived that the world had lost the sacramental view of reality; that is, the ability to see the supernatural in the natural. In her stories, grace arrives so disguised you almost miss it, because it’s not a pretty thing. Terrible characters are not abruptly made Tide-clean. Grace meets the characters where they are, and where they are in Flannery World is usually a gritty, squalid place.

It’s why she used almost comically disfigured characters; she categorically refused to do any tidying up. As she said, “Truth don’t change according to your ability to stomach it.” And she does more than tell the truth; she deliberately seeks out the oddest of the odd, as though she’s running a literary freak show along the back fence of a country carnival.

Why did she make her stories so deliberately clanking to our sensibilities? In her own words, “to the hard of hearing, you shout.” The audience she envisioned was so far from an Incarnational worldview that she had to use the most bizarre, displeasing, unconventional characters. We have our own bizarros in this age, who are as distasteful to us as The Misfit was in hers (think furries). Flannery used that distaste to shake us in our complacency. In Flannery’s stories, no one was so far gone as to escape God’s hounds.

To the young generations, Flannery will be speaking in an unfamiliar dialect, but I think they will get the oddness of her. The dynamics of the post-Christian culture drive young people inward, where they became more acutely aware of their differences and isolation, painfully so. The outrageous, eccentric, crippled characters will call to them.

And that’s the prize of this film: to introduce Flannery O’Connor to the generations who’ve never heard of her and are unlikely to study her after the Great Cultural Purge of 2020. Though the short stories are not carried to completion in the movie, they are provocative enough to drive viewers to the body of O’Connor’s work.

For Catholics especially, an exhumation of Flannery’s stories and letters may be refreshing. O’Connor works like muriatic acid on stone, burning away the excess. In this Era of Nice, someone who cuts to the bone is both rare and welcome. Flannery was particularly equipped to perform the operation. She died young, at 39, after having had her life curtailed by the advance of lupus. She was intolerant of dross by nature; and in her disability, I imagine she would rather have lost a limb than say anything sentimental or only partially true.

That has got to be a tall glass of minted iced tea for most of us.

Wildcat begins its theatrical run on May 3. With the caliber of its stars, it should get some good play.

Watch the trailer here.

Read your way to Flannery appreciation here:

Ten of the Best Flannery O’Connor Short Stories

The Complete Stories.

Personal postscript: I began consuming the short stories for this review. And with the help of my favorite Flanatic, Monica Ashour, I think I’m acquiring the taste.

0 Comments