OPINION –

The depth test of any movie is how long it takes up residence in your mind afterward. Three days later, The Jesus Revolution is still rattling around in my brainpan, so it passes the test.

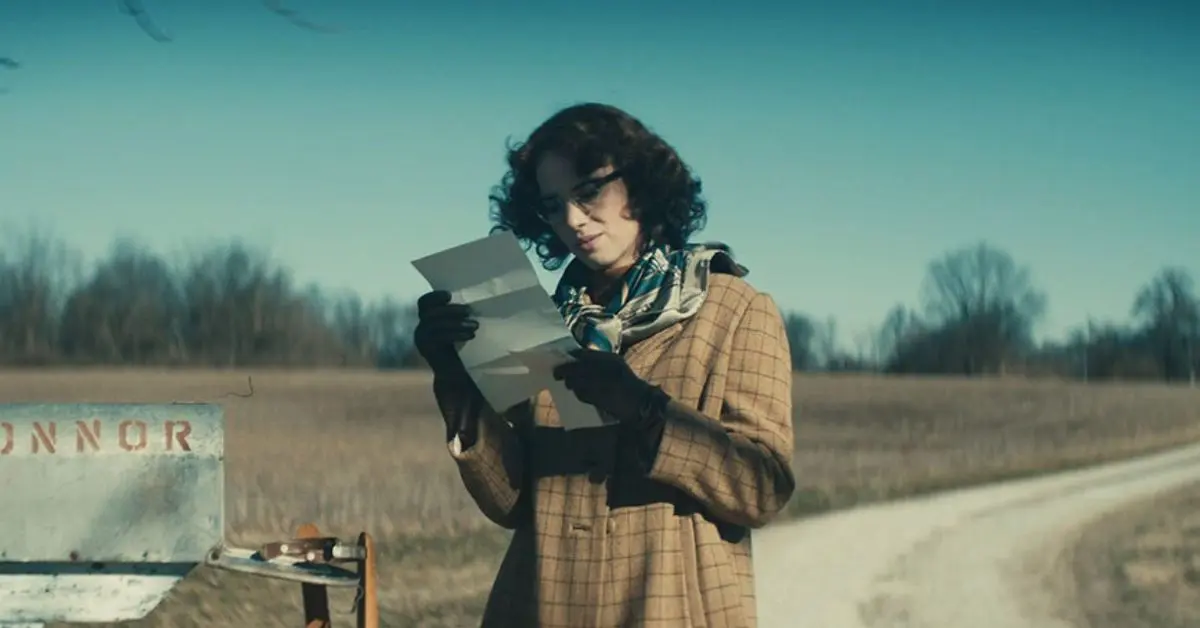

I just wonder why I didn’t like it more. It had all the elements of something I’d love: Jesus; the marvelously gifted Jonathan Roumie of The Chosen (plus a cameo appearance by Paras Patel, everyone’s favorite obsessive-compulsive apostle from the same series); the beautiful beaches of southern California; and redemption. Recipe for success; but it left me strangely unaffected.

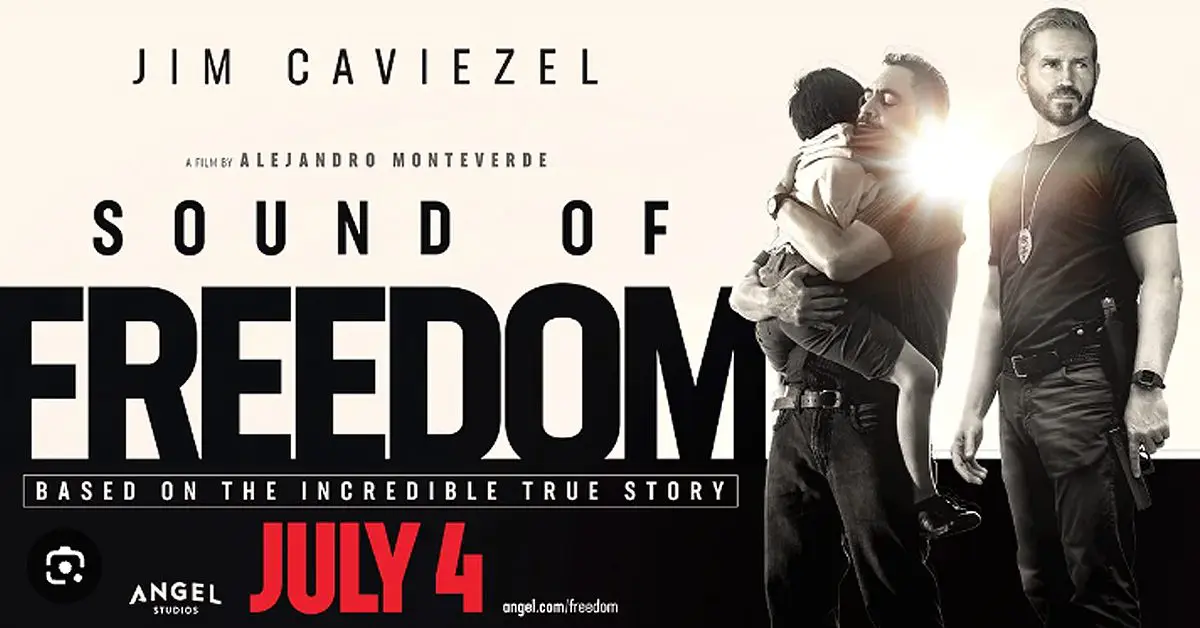

For me, Roumie was worth the price of admission all on his own. I was loathe to see him play anyone other than Jesus because I thought it would ruin The Chosen for me, but it did the opposite. Roumie has an uncanny ability to make love visible. You can see love happening in his gaze on lost souls, as both a very human evangelist in this movie, and as the Great Evangelist in The Chosen. Roumie is better even than Jim Caviezel at personifying love onscreen (but Caviezel wins hands-down at suffering).

Here’s the story: the magnetically appealing Lonnie Frisbee, hitchhiking south from Haight-Ashbury in 1968, is introduced to southern California pastor Chuck Smith. Smith is impressed by Frisbee’s love for lost souls and puts him up front to preach in his fledgling Calvary Chapel. Frisbee had already dabbled in the occult, and an acid trip had launched his preaching career, so he understood those on the younger side of the Generation Gap. One of those, a lost and drug-addled Greg Laurie, becomes a protégé of Frisbee and Smith, cleans up his act, and is launched on his own preaching career.

Soon, the tiny Calvary Chapel is bursting at the seams with young people, and baptisms become exuberant outdoor festivals at the nearby Pirate’s Cove. Frisbee performs several miraculous healings and seems to get infected by the spirit of self, which ruptures the relationship between him and Pastor Smith. Meanwhile, the “Jesus Movement” becomes famous, appearing on the cover of Time magazine.

So, there are four story lines: the revival itself, Lonnie Frisbee, the trajectory of Calvary Chapel under Chuck Smith’s pastorage, and Greg Laurie’s early life. (Laurie is, today, the evangelical pastor of a megachurch in Riverside, California, and the international Harvest Crusades.) It is, perhaps, the more or less equal weight given each story line that hinders the movie. I was most interested in Lonnie Frisbee, so the Greg Laurie story seemed a distraction. For anyone attached to Greg Laurie, perhaps the Chuck Smith story was a distraction. I think the writers might have picked a lane.

The pivotal line in the movie, the key that makes it all make sense, is delivered when Pastor Smith first meets Lonnie Frisbee. Smith is completely bewildered by the hippie movement, but Frisbee responds, “They’re on a quest. They’re searching for God. How can you not see that?”

So the movie demands, at the outset, a sympathy with the teenagers of those years who were so desperately unhappy and searching. That was a stretch for me, as I always wondered why anyone would find drugs appealing.

The answer, of course, is the addictive element, the nature of sin that captures a soul and won’t turn it loose. There is a brief reference to it when Frisbee heals a woman who has tried and tried unsuccessfully to get off drugs. It hearkens to the story of the woman who spent all her money on doctors to cure her hemorrhage but was still bleeding after 12 years. It’s a quick moment in the film, but most everyone resonates with the desperation that results when we try to solve a problem that is just too big for us…and the wonderous joy when God steps in.

For many viewers, the movie was a walk down Groovy Lane, bringing back music and memories of the late ’60s and early ’70s. Even as a teenager in the early ’70s, I was mildly repulsed by the popular culture. I was too young to understand the mass deformity being wrought by contraception, the unspoken footnote of “free love,” but I sensed the deception.

The theme for the kids in the movie was Timothy Leary’s line, “turn on, tune in, drop out” (the turn-on being LSD for Leary). There were no sex scenes in the movie, an omission for which I was grateful, but the drug culture was part and parcel with “free love” and the great lie about human sexuality. While the Jesus Movement was rolling on the West Coast in ’68, Woodstock was rocking on the East in ’69.

The challenge of representing religious experience on film is that it can’t be seen or heard. The only way to show it is to portray the person before and after and let the contrast speak for itself. This was beautifully done in The Chosen with Mary Magdalen. You see her tragic depravity, her extreme anguish and need to escape the horror of her life, then you see her after encountering Jesus, in her true beauty and calm and compassion for others.

The difference between that conversion and the ones in The Jesus Revolution is time. In a two-hour movie with multiple plot lines, conversions can only take up a few seconds on screen. New life in Christ is shown by a hug between the baptized and the baptizer as they stand in the ocean. You have no real sense that the person has been changed, no sense that they are coming to a deeper knowledge of Christ.

The closest the movie came to portraying the true religious experience of conversion was the brilliant handling of Greg Laurie’s baptism. As he is submerged, the movie shows him sinking a great distance, an unsustainable distance, like a death. As he looks up, he sees a hand, ready to pull him up out of darkness into light. “All of us were baptized into Christ’s death in order that we, too, might be raised from the dead to new life.”

Many of the original Jesus freaks did follow Christ fervently for the rest of their lives—Greg Laurie, for one. I have also heard that some eventually became Catholic, a process that takes much more time than a one-time dunking in the ocean, as joyful as that experience may be. Growing in faith is a process rather than a moment, and whenever those initial experiences lead to new life in Christ with His bride, the Church, they must be accounted a work of the Holy Spirit.

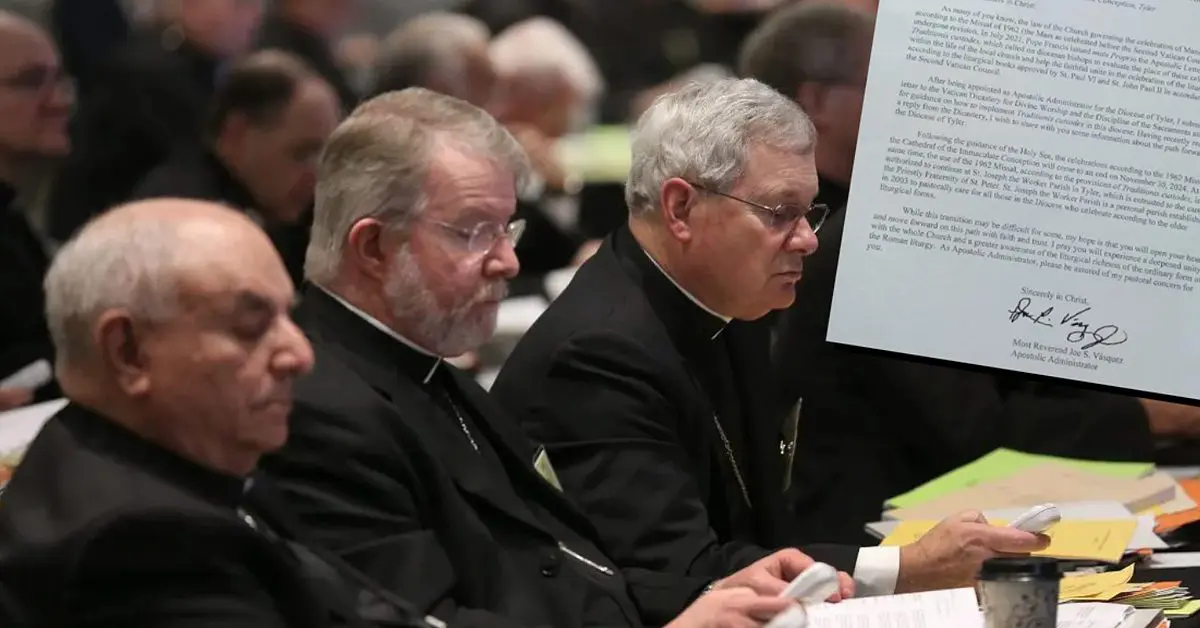

In our contemporary ecumenical mindset, we are prone to look at all Christian religions as equal. And a Christian life, even one without the sacraments, is vastly superior to a worldly life with all its seductive and deadly distractions. But the Eucharist is always and forever the source and summit of the Christian life, of all Christian lives. The moment of conversion can never stop drawing a Christian to Jesus Christ in the Eucharist. So, I’m left a bit wanting after a Protestant conversion story. It’s like stopping at the soup course and missing the entree. The point is driven home when Pastor Smith offers a communion service, emphasizing that this is a representation of Christ’s body. I wouldn’t be Catholic if that didn’t make me sad.

Movies and series of recent years seem to partake of a certain easy joke line, “the frozen chosen.” Calvary Chapel before Lonnie Frisbee was represented as sparsely attended by frowning fossils of the square generation. It’s the same plot mechanism as the town of River City before Professor Harold Hill arrives to lead the 76 trombones. But really, was the church completely devoid of any joy in the Lord, any energy for mission, until the hippies arrived?

The older members can’t have been as dead as they were represented; something was drawing them to church every week before the hippies came, in the days when it was possibly painful to go, when the church was quiet and the pastor a bit uninspired, the singing a little thin. They were searching, too; they were on a quest, too. They were holding down the fort for the arrival of the next generation.

The older members of Calvary Chapel also experienced a conversion, which was underscored by one of the frowniest members going to sit with the hippies. I loved that moment of acceptance, but I think it would have been even more powerful if the older members had not been comic book villains.

Jonathan Roumie makes this movie compelling. Where the frozen chosen are overplayed, Lonnie Frisbee is played with delicate complexity. The man Lonnie Frisbee was a flawed man with extraordinary gifts. Though not shown in the movie, Frisbee had illicit sexual affairs and struggled with drug use. That makes his “come to Jesus” scene even more poignant, as he tearfully begs in prayer for God to keep using him. Frisbee’s struggle with corporal sin is omitted from the film, but it’s that element that nuances Roumie’s portrayal of him and adds layers that don’t need specific explication for family audiences.

The film was initially announced in 2018. Filming began in March 2022, one year before a regularly scheduled chapel service on the campus of Asbury University in Kentucky blossomed into a full-fledged revival on February 8, 2023. The timing is beyond remarkable; it’s enough to hear dove’s wings. The movie was a bit incomplete for me as a Catholic, but it’s hard to not see the Holy Spirit at work renewing the world.

The Jesus Revolution was released in theatres on February 23. It continues its run, as ticket sales have been encouraging.

Sheryl Collmer is an independent consultant for several non-profit organizations. She holds a Masters in Theological Studies from the University of Dallas, as well as an MBA. She lives in the diocese of Tyler, Texas and also serves as CFO, co-coordinator of Region 8, and national news editor for CORAC.

0 Comments