OPINION –

Why is the Civil War the most interesting period in American history? Why has a book like Gone With The Wind been translated into dozens of languages around the world (including Korean, where it comes already loaded onto new tablets)? Why are Civil War battles re-created all over the country, with re-enactors investing thousands of dollars in their kit? Why do millions of tourists visit Gettysburg, and why is that battlefield featured in movies like Remember the Titans as a turning point in the lives of those who come?

The Civil War is ours, for one thing. We didn’t fight it in Europe or the Pacific, but in Richmond and Atlanta and around Washington DC; New Orleans, Baltimore and Nashville. It was fought in the towns, woods, swamps, prairies, rivers, churchyards and neighborhoods of America, our homeland.

As a thought exercise, imagine war breaking out in the United States today. It would likely be about personal liberties, the power of the Federal government, the Constitution’s primacy, the berserker sexual activists and traffickers, and abortion. In other words, it might be ignited by any number of issues, but eventually it would come down to the meaning of life, and its protection.

In the 1850s, there were tensions about the rights of states, equity in Congress, sectional tariffs and imports, and slavery. After a few years of war scoured away the details, it became a more single-minded war for the abolition of slavery. One could say that the Civil War came down to the meaning of life, and its protection.

The primary lessons I draw from the War are these: nothing less than the meaning of life is worth a war, as it costs more than one can possibly imagine in peacetime; extraordinary leadership is required to make effective the sacrifices of soldiers; and moral authority is absolutely necessary to prevail over a stronger enemy.

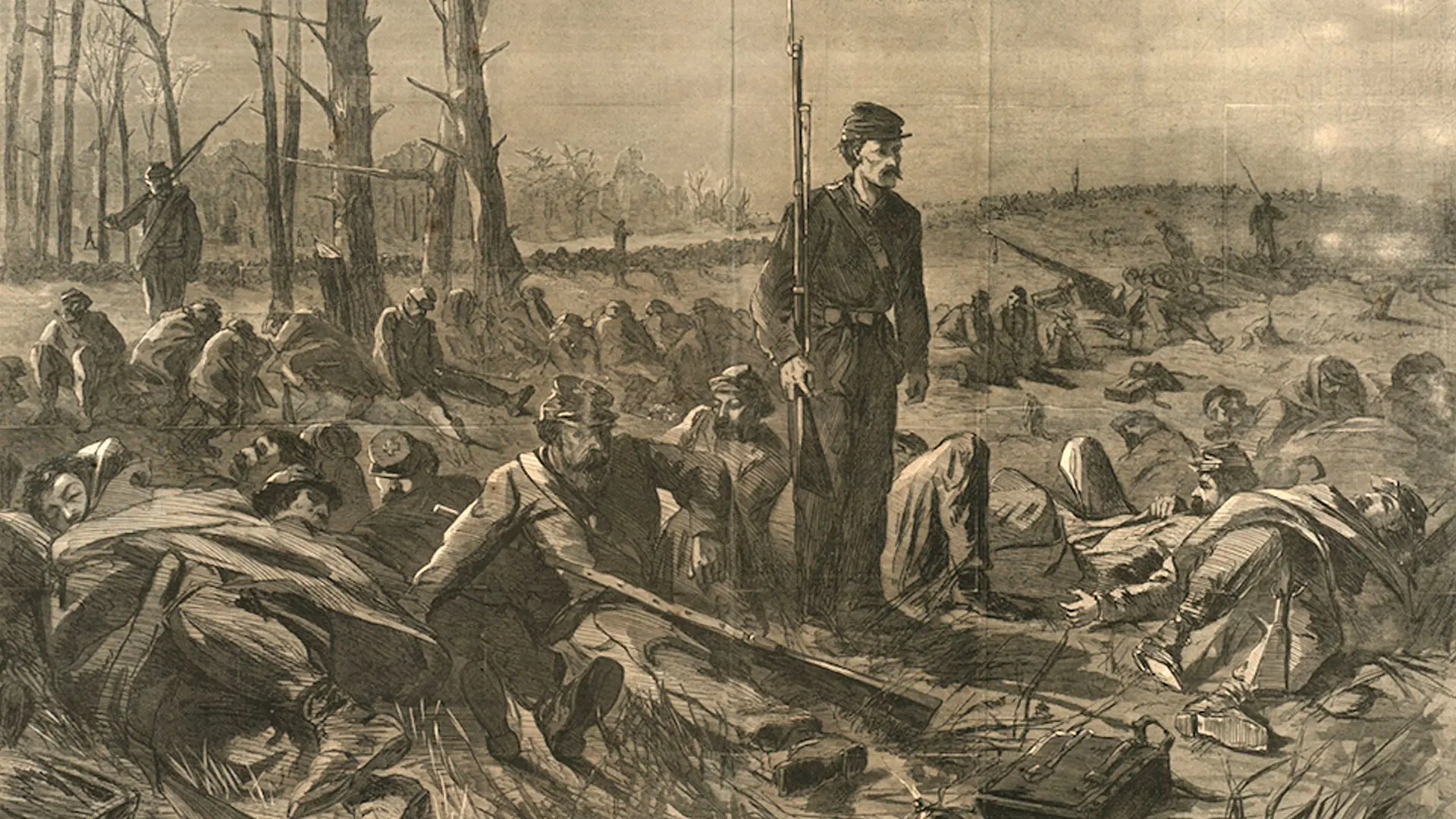

The Cost

In the 1850s, Americans weren’t thinking, “We’re living in the run-up to a war that will destroy us for generations to come.” There were sectional conflicts, journalists fanning the flames, and speculators eyeing the profit potential of war, like today, but most people were engaged in their daily pursuits, hoping the conflicts could be settled reasonably. Without the agitation of social media, you’d think there’d have been a better chance of peaceful resolution, but whenever influencers manipulate emotions, civil war can be lurking. If the issues concern your livelihood, your family, or your religious convictions, the kindling is dry.

The caning of Charles Sumner on the Senate floor in 1856 is a perfect picture of the descent into chaos. Sumner, a Republican from Massachusetts, had given a violently angry speech in the Senate, lasting two days, calling his enemies things like “drunken spew and vomit.” And then he got nasty. Senator Stephen Douglas remarked quietly, “That damn fool is going to get himself killed by some other damn fool,” and that was nearly the case.

Representative Preston Brooks of South Carolina entered the Senate chamber and issued a sort of a medieval challenge: you’ve slandered my countrymen, and honor demands a reprisal. He then struck Sumner over and over with a gold-tipped cane to the point of unconsciousness. Sumner suffered injuries that lasted for years. Brooks was fined $300, re-elected to his seat, and received canes from appreciative supporters all over the South, which enraged the North possibly more than the actual incident.

It would be several more years before the first shots were fired, but in retrospect, it was clear that the conflict had moved from philosophies to passions, from the oratory to the boxing pit. More and more people were starting to anticipate war, even desire it, as a way to redress grievances that weren’t being otherwise resolved.

Once the shooting started in 1861, the veil was torn. Actual war far exceeded anyone’s expectations of the human cost. In 1861, as the first full battle was shaping up at Bull Run, near Manassas Junction, Virginia, Washington’s elites rode out in buggies with picnic hampers to watch the match. Women with their parasols, men with their cigars, were not expecting to see entrails and severed limbs. It was meant to be an afternoon’s thrilling entertainment, capped off by the spectacle of upstart Rebel soldiers fleeing at first glance of the imposing Federal army. There was a grave awakening that day, as the Rebels stood their ground and fired back rather insistently, causing the buggies to careen back to the city.

It was a nasty surprise to the Southerners, too, though they held the field that day. They had similar illusions of a war easily won against a sissified opponent. In one of the opening scenes of Gone With The Wind, a young man from Georgia boasts, “Everyone knows one Southerner can whip ten Yankees!” That sentiment was widespread, even used to bolster Southern soldiers before battle, according to an eyewitness at Bull Run.

Bold words took a mortal hit in that first battle. There were 4,500 casualties at Bull Run, which shocked both armies and civilians. No one yet realized that future battles would dwarf that, in numbers of killed, wounded and missing men. The horror to come was like a hurricane forming in the Atlantic, spinning ashore with a punch no one expects.

Battle of Antietam, Antietam National Cemetery

Leadership

What kept the war going as long as it did was probably leadership. Both North and South had skilled, courageous, persevering soldiers, but they could not have effectively deployed their strengths without good leadership. You may have citizens itching for war, eager to fight a clear evil, but without fine leadership, that passion can’t be productively mobilized on a grand scale.

Everyone knows the names of great Civil War leaders, even if they don’t know exactly what they did: Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, Ulysses S. Grant, and William Tecumseh Sherman, in addition to many lesser-knowns who performed magnificently.

The South, with far fewer resources, and a smaller population pool to draw from, nevertheless performed well at the beginning of the war, quite likely due to superior leadership. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson was a standout from the very first battle, where he gained his nickname from his stern refusal to back down when others fled in confusion.

Robert E. Lee didn’t command an army until a year into the war, but his presence was mightily evident once he did. His unconventional battle plans that triumphed by sheer audacity made him a symbol of canny genius and sober courage. Faith in his leadership kept the Southern armies in the field long after ultimate defeat had become inevitable. Even as he negotiated the surrender at Appomattox Courthouse, his starving, barefoot men pledged to fight on, if he wished it.

The Union armies, in contrast, were plagued by poor leadership in the first few years of the war. President Lincoln initiated five changes of military leadership before giving overall command of the US Armies to General Grant in 1864. Northern soldiers, bitter that their sacrifices in battle kept being undone by the bad decisions of their leaders, were eager to exact retribution from the South. General Sherman’s troops pillaged Georgia and South Carolina, under orders to demoralize and impoverish the civilian South, to cripple their will to fight. Though Grant was called “the Butcher” in the press, for feeding men into battles to overwhelm the enemy with sheer numbers of bodies, he produced victory after victory, proving to be a leader worthy of his men.

Moral Authority

Starting a war is somewhat easy; it takes the sustained inflammation of emotions and an outraged sense of justice, hopelessness, and a perceived threat to one’s family. To carry on a war, though, over a long period of time when the casualty lists grow longer, a people must hold moral authority. You have to know that the cause you’re fighting and suffering for is just, and that God fights with you.

Both sides in the Civil War were initially convinced of God’s favor, but when opposite principles face off, God can only be found on one side, the side of Truth. For the early years of the war, when Northern soldiers were being poorly used by their leaders, their endurance was fortified by the sense of being on the side of right. By the time the war reached the long, sad slugfest of 1864-5, the Union was well convinced of the morality of their cause. While the determination of the South had not flagged, the supernatural power that accompanies God’s overarching will was absent.

The Civil War proved that secession is possible, and even Constitutionally defensible. Secession itself is a non-violent act; it’s like leaving a party when the drinking gets out of hand. But once the Federal government acted to forcibly retrieve the seceding states, they had to build from scratch an army, navy, communication system, currency, constitution and law. States that remained bound to the Federal government had those institutions already in place. With such a disadvantage, a seceding state had best be on the side of Truth.

Given the evil rampaging through the world right now, searing a jagged path straight through marriage and the family, with every sign of accelerating, there will be a fight. Evil does not retreat, unless it is to give its opponents time to grow complacent before the next onslaught. It would be prudent for us to plumb the wisdom that our particularly American Civil War left us, as we contemplate what is to be done. The meaning and protection of life is at stake, and the kindling is dry.

Sheryl Collmer is an independent consultant for several non-profit organizations. She holds a Masters in Theological Studies from the University of Dallas, as well as an MBA. She lives in the diocese of Tyler, Texas and also serves as CFO, co-coordinator of Region 8, and national news editor for CORAC.

0 Comments