When the Cathedral bells swung five minutes before Mass last weekend, they seemed to know. The Ave sung with the Rosary was so mournful, you’d think someone had died. A light went out in Tyler on Saturday.

The seat of the bishop is empty; the coat of arms will be replaced. We have all been dealt a blow that fails in justice, compassion, and charity. The loss of a bishop always hammers the people, but the loss is usually to death, which can still be celebrated. This loss is unmitigated.

Our Protestant friends in Tyler have been following the disturbing events since the Apostolic Visitation in June, and we all received calls and texts from them on Saturday. Bishop Strickland is honored in this mostly-Baptist town as a true follower of Jesus Christ.

One Protestant friend asked me what church I would be going to now; but we don’t roll that way. We can’t leave our Church; where else would we find the Bread of Life? Still, we are fed up and overflowing. We have no recourse for injustices committed at the highest level. Does anyone in the hierarchy actually care that we are serially battered and grieving and yet we still show up for Mass, choir, religious education, serving the destitute, and all the other things that keep a parish running?

Most of us who have moved to Tyler in the last three years have been here before. It’s the reason we packed up our U-Hauls and headed to this nondescript little city off Interstate 20: we’d already been betrayed by our local churches. We heard Bishop Strickland on the radio and saw the iconic photo of him processing with the Eucharist on the busiest streets of Tyler while everything else was shut down and denied to the faithful in 2020. He was all-in, and he was not about to let the Church go down on his watch. We recognized the voice of a shepherd; he spoke Christ.

Some families left their former homes in RVs to get to Tyler more quickly. Some lived in hotels for months until they could buy a home. Some sent one spouse ahead, while the other stayed behind to sell the house—or, in the case of Canadians, to comply with immigration requirements. Many didn’t have jobs yet in Texas, and some are specialists that will now always be underemployed in the smaller economy of east Texas.

But we got here as soon as we could: singles, families, big families; and it’s been better than we imagined. We found beautiful, reverent liturgies, more faithful Catholic events than we could shoehorn into our schedules, and a growing community of other people looking for the best of the Church and ready to pitch in to help.

We heard the voice of a shepherd and took our chances. And as much as we loved Bishop Strickland from afar, proximity was better. He learned our names, came to our homes, showed up at events we organized. We never stopped being thrilled to see him personally, but we got more accustomed to it, seeing him at Walmart, local restaurants, on the city square, in the neighborhood, at our social events.

One day, I was out walking when the bishop drove by. He recognized me, put down his window, and made pleasant for a few moments before driving on. So very simple, but totally unique in my experience.

Once, sitting with a group on the patio of a local restaurant, the bishop saw us from his table and came out to greet everyone and bless us before returning to his table. The remarkable thing was that he knew us from across the room. What we need is so simple: to be known and valued by our shepherd. This is not an experience that should be rare.

Most bishops know the names of their superstars. I don’t think any bishop has ever known my name, and no wonder: I’m not a major donor; I don’t do critical work. And yet, not only does Bishop Strickland know my name, he has an idea what I am about. We got to see our bishop at least once a week, sometimes more. Relationships take that kind of time and consistency. You can’t know your shepherd if you only see him once a year in a crowd of hundreds.

In other dioceses, being “pastoral” involves committees and meetings and budgets. In Tyler, “pastoral” meant being friends. Perhaps Bishop Strickland is particularly gifted in his people skills, but I think it’s more likely that he simply takes his God-granted position seriously. When the pope advised bishops to “smell like the sheep,” it was coarse phrasing, but it’s what Bishop Strickland did. He knows us, knows our families, knows our hearts. He guards our spiritual well-being. He never tires of pointing us to Jesus, not only in words but by his hours in Adoration. He is a bishop not as an administrative job description but as an all-consuming vocation.

It’s a gut punch to lose Bishop Strickland, and it recalls, for most of us, a long line of them. Betrayal by Church bureaucrats is a special kind of excruciating. A person or family sacrifices themselves to follow Christ, then a hierarch sells them out as though their life’s sacrifice had no meaning at all. If I asked for a show of hands, I’d bet millions around the world would testify to this experience.

And if there are any who haven’t experienced it personally, they’ve experienced it corporately, thanks to people like McCarrick and everyone who covers up for them, right up to the top. They worked over the whole Catholic faithful and left us bleeding in an alley.

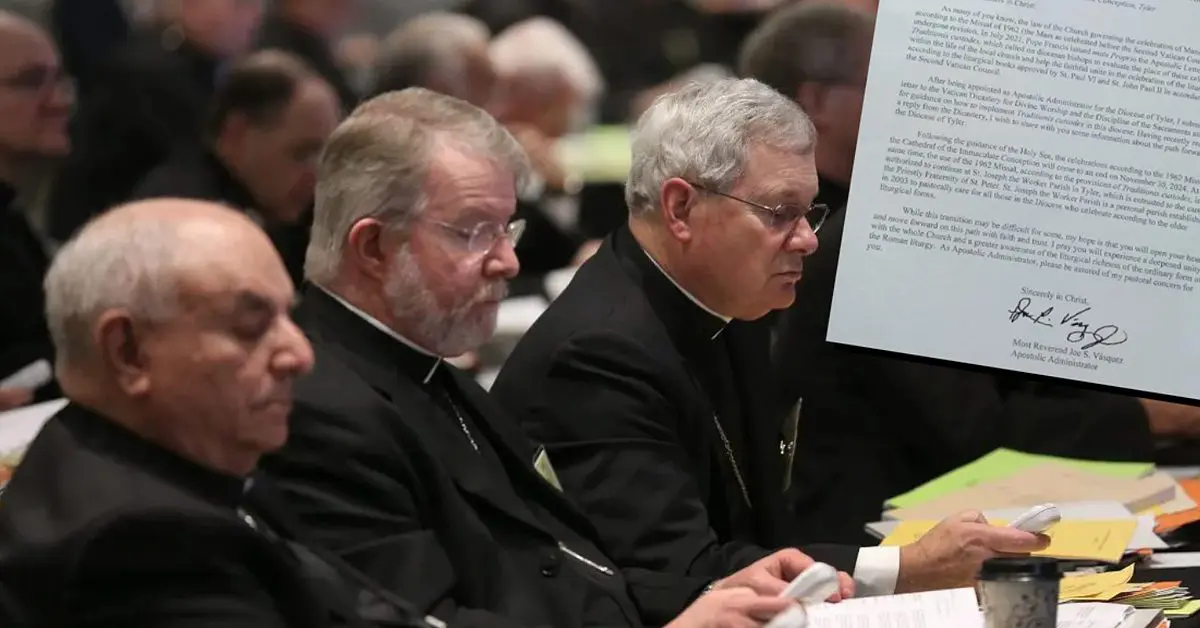

How can we forget the revelation of the McCarrick filth in 2018 and the following USCCB meeting, where, kowtowing to the request of the pope for more time to douse the flames, the bishops declined to take any action? We were abandoned by every bishop who could not draw a distinction between true authority and guilty cover-up.

That happened to be the same year that Bishop Strickland rose above the timidity of the bishops hiding in the Waterfront Marriott from the terrorists across the street who were praying the Rosary. Bishop Strickland crossed the DMZ—the only bishop to do so, mind you—spoke with the scary laypeople, and joined them in prayer. From that moment, people nationwide began to gravitate toward a shepherd who cared.

The faithful have had to swallow so much utter horse manure over the last few decades. Instead of someone (that would have been the job of the USCCB) grabbing the reins and halting the runaway cart, it just careens downhill faster. Bishops who care more about the souls in their care than political influence and their own advancement are few, and one of those few just got beggared.

I wish for every Catholic the experience of being protected and loved by their shepherd, as Christ intended. The bishop-as-CEO model is bankrupt; neither the shepherd nor the sheep get what they are intended to have. The bishop may get props from the business community for his acumen or fundraising, but he doesn’t get the full-hearted love he needs—because his flock doesn’t know him. And the flock is left vulnerable and alone.

Some say that the influence of Bishop Strickland in the Church will do nothing but grow now that his diocese has been ripped away. I believe God will indeed bring good from the devastation. But meanwhile, the laity is suffering badly—not just in Tyler, but everywhere people heard a true pastoral voice and enjoyed the protection of a shepherd, even if on the radio.

Sheryl Collmer is an independent consultant for several non-profit organizations. She holds a Masters in Theological Studies from the University of Dallas, as well as an MBA. She lives in the diocese of Tyler, Texas and also serves as CFO, co-coordinator of Region 8, and national news editor for CORAC.

0 Comments