We hardly know how to measure strong women anymore; modern feminism has so bent the ruler. Feminism, once a virtuous philosophy worthy of St. Edith Stein and St. John Paul II, has become a cesspool that Catholics, women and men, instinctively avoid. So, is the tale of a particularly strong woman, Mother Frances Xavier Cabrini, who set in motion more genuine help for those in need than anyone in this country’s history, a “feminist” tale?

I think not, and here’s why. Feminism, as we understand the movement today, is self-promoting, grasping at awards rather than rewards, and allowing for the elimination of anyone who would get in the way, even accidentally—like an unborn child. Modern feminism is a spirit of combat and taking rather than love and giving. It’s a land grab.

Not so Mother Frances Xavier Cabrini, the first American saint and the subject of a new film, Cabrini, distributed by Angel Studios. Mother Cabrini cared nothing for herself or her sisters, who were willing to endure poverty, insults, and violence for their mission to the Italians who’d come, full of hope, to America for better lives but found ruin instead. There was not a drop of “me” in Mother Cabrini.

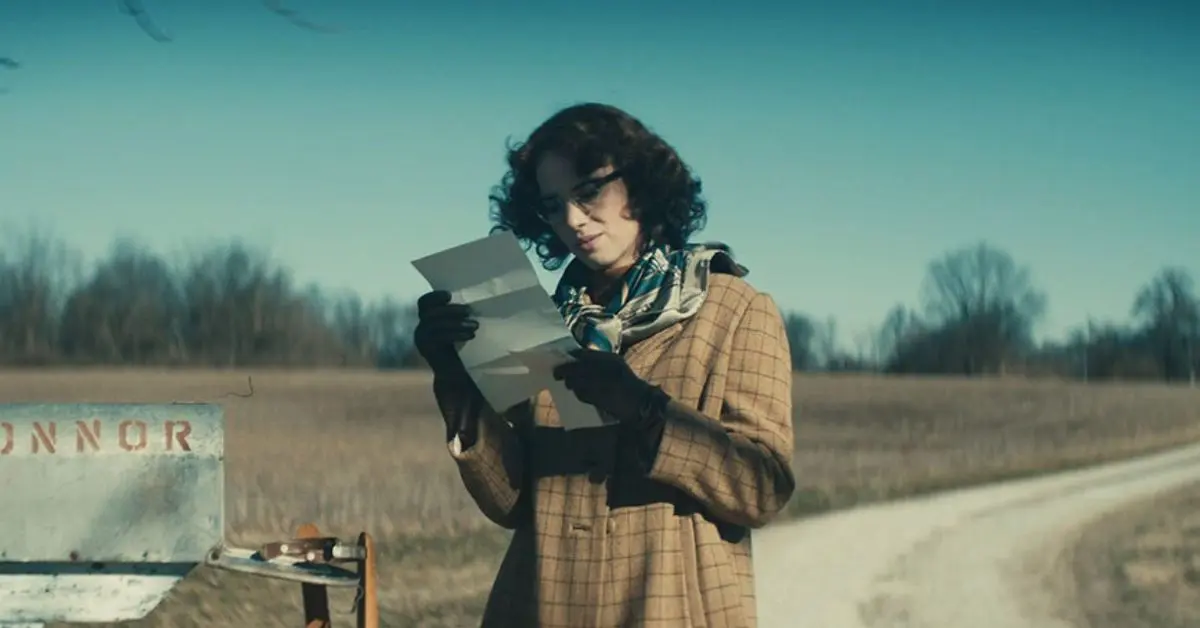

And though the movie revels in the iron-strong character of this fragile woman, it never sells the idea that she deserved anything for which she didn’t work to death. You can get fatigued just sitting in your seat eating popcorn, watching what Mother got done in only a few years. (The movie covers the span from Cabrini’s arrival in America in 1889 through the founding of Columbus Hospital in New York in 1892.)

In a nutshell: Sister Francesca, a successful teacher, wants to be a missionary. The pope convinces her that she is most desperately needed in America, where Italian immigrants have fled to for jobs and golden opportunities but have wound up in slums, sick and impoverished. Their living conditions are so abject—25 people to a room, sleeping in shifts—that the infectious diseases of the time, typhus, tuberculosis and cholera, rip through the immigrant communities, leaving orphans with no care at all except gangs of children.

The pope at this time was Leo XIII, called the “Pope of the Workers.” He had a heart for men striving to provide a good life for their families but who were unjustly used. When he first met Mother Cabrini, he had a whole box of letters from Italian immigrants, grieving their dashed hopes, that he called his “tomb of dreams.” He was not initially in favor of an all-women organization going into mission territory, but if Cabrini was set on it, he preferred she start in America, where Italian orphans slept in doorways or in the sewer tunnels.

Accepting the challenge, Cabrini sails with her six Missionary Sisters of the Sacred Heart of Jesus to New York, where the local archbishop has meanwhile withdrawn permission for her project, the priest commissioned to help her has slipped into a barely-functioning depression, and the Irish political machine is not about to allow Italians to rise.

In zeal for her mission, Mother Cabrini goes up against some Big Boy networks, both secular and ecclesiastical, and they block her easily. But as St. Teresa of Calcutta once noted, true authority comes from the trust of those who know that you serve them. The men who originally opposed Cabrini had power, but the nuns who risked everything to rescue children and families had authority. That kind of moral authority eventually wins. (Good news for us who are hanging on by our fingernails.)

There are a few feminist triggers for those looking for them, as when Mother tells her sisters, on the eve of their departure for America, that without the support of men, they will have to rely more on themselves. Does that exude an aroma of feminism? Or when Mother tells the mayor of New York that men could never do what women do. Okay, that might smell a little feministic, but it’s nothing most women haven’t said (and their husbands acknowledged) at labor and delivery.

Our disgust with modern feminism shouldn’t blind us to the fact that women accomplishing things in the world on their own has always been an obstacle course. The lies of modern feminism are certainly to be rejected, but it is nevertheless true that women face a different world every day than men do, a world in which they are more vulnerable and easier to defeat. Mother Frances was a lioness, but she didn’t march out carrying a banner for womanhood. She saw a wailing human misery, and she ran to it. That’s all.

This movie is a work of art, and I fell in love with its artistry. It is a pageant for the senses. Is there a film term for the succession of still images any one of which is worthy to be hung in a gallery and admired, every frame a masterpiece painting?

One example: the sisters are in the dingy, crowded hold of a rolling ship at sea. (Even the hold is shot with a certain stark beauty.) It’s dark inside, and Mother sits near a porthole, looking pensively out at the ocean. The exterior light frames and makes brilliant that solemn Italian profile. The camera moves on seamlessly, as though dissolving the window, to show the tiny ship on the vast ocean, lit by crepuscular sunbeams. The tender beauty of it challenges my ability to verbalize, and the movie is one unspeakably powerful scene after another. You’ll see.

The artist who achieved this visual magnificence is Gorka Gómez Andreu, part of the dream team who made Sound of Freedom such a thing of beauty. He has taken his gifts even further in Cabrini. I have to assume the man is a perfectionist, in the best sense; no scene of the movie, whether in the Italian countryside, the bleak New York tenements and sewers, or the baroque furnishings of the papal office, was shot casually. Every scene piques your senses.

Likewise for the snappy editing, intriguing camera angles and cutaways, the dramatic use of light, and the heartrending music. The cold open may be the most compelling start to a movie since Jaws.

Angel Studios is definitely on a roll after the colossally successful Sound of Freedom last summer. The budget for Cabrini was $30 million, quite modest as movies go. But it is set up for great success, with a compelling story and veteran actors like John Lithgow, Giancarlo Giannini, and David Morse. The 38-year-old actress Cristiana Dell’Anna, who shines as Mother Cabrini, is well-known in Italy but a surprise to Americans. She’s rather perfect in the role, as her facial expressiveness deepens the portrayal of a woman who didn’t waste words. It is her face that tells the story of Cabrini’s passion and growing resolve.

Mother Frances, though intimidated at first by united fronts of unsympathetic men who opposed her very presence in their midst, developed an exemplary Hard Stare. When a woman of God fixes that intent gaze on someone who should know better, arrogance melts. Millions of former Catholic schoolboys can attest to the dynamic. By saying nothing and looking into their hearts, Mother caused men to examine themselves by the reflection in her eyes.

As Mother’s empire-building (she called it “the empire of hope”) grew, very powerful men in the self-satisfied ruling conclaves of places like New York and Chicago fell into reluctant friendship with her and wound up being her most enthusiastic benefactors.

Cabrini is basically an action movie, a David and Goliath tale. You can’t help but cheer for the underdog who feels God’s call so intensely.

I did wish that reliance on God was more explicit in the movie. I yearned for a glimpse of a monstrance, showing that the Eucharist was the source of Mother’s life and mission, as it certainly was. St. John Paul II said about Mother Cabrini, “Her extraordinary activity drew its strength from prayer, especially from long periods before the tabernacle.” What a gorgeous scene could have been crafted of Mother in adoration by that marvelous artist behind the camera!

The director, Alejandro Monteverde, is definitely Catholic, so it must have been a conscious decision to merely imply prayer rather than represent it outright. Frankly, I think it was an omission of the very heart of Mother’s story and a missed evangelization opportunity; but perhaps that was not the vision.

Cabrini is a rough-and-tumble adventure, not a devotional, and for that, it’s top of the class. It will capture young viewers with the risk and excitement of the Christian life, so different from their assumptions about a dull and constricted existence under Christ.

In that sense, it is perhaps the evangelization that is needed most.

Cabrini opens in theaters across the country on Friday, March 8. Advance tickets are on sale at Angel Studios. You can view the trailer here.

[Editor’s Note: For those interested in learning more about the life of St. Frances Cabrini, Sophia Institute Press is releasing three new books about her life: Mother Cabrini: A Heart for the World (a children’s book), The Mother Cabrini Companion, and The World Is Too Small: The Life and Times of Mother Cabrini.]

0 Comments